Flipping Rates Near Historic Highs, but Flippers are Playing a Different Game

Home flipping activity[i] is on the rise. The rate has increased on a year-over-year basis for 12 consecutive quarters, and on a seasonally adjusted basis is now at the highest level since we started keeping track in 2002. But the flipping game is different this time around, with short-term investors focusing more on adding value than speculating on prices.

In this CoreLogic special report, we take a deep dive into home flipping. Not only do we investigate flipping rates nationally and across U.S. metros, we also estimate the gross economic returns[ii] to home flipping at the national level, and test to see what factor is most correlated with such returns.

Home Flipping Rates Up Nationally, Highest in Sand States

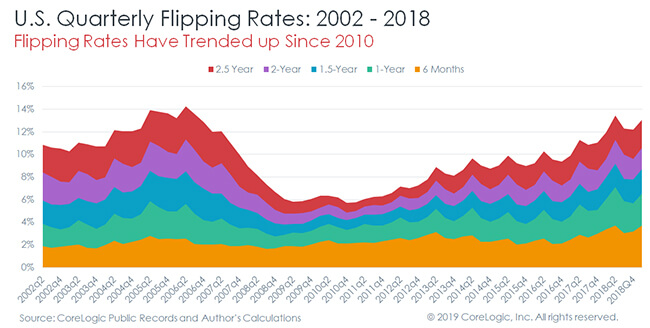

By the fourth quarter of 2018, the flipping rate in the U.S. reached 10.9 percent of all home sales – the fourth highest rate since we started keeping track in 2002, just behind the first quarter of 2018 (11.4 percent, the highest on record), the first quarter of 2006 (11.3 percent), and the first quarter of 2005 (11.1 percent). The flipping rate in the fourth quarter of 2018 was also the highest rate for any fourth quarter in our flipping data series.

While we use the two-year definition of flipping in the remainder of this report, it’s important to also look at how other measures of home flipping have trended over time. As we can see from Figure 1, the fluctuations in flipping activity over time has predominantly occurred not from the involvement of short-term flippers (buying and reselling within 6 months), but rather from longer-term flippers (one year or more). This could be for a few reasons that we’ll investigate in a future report, but it could be a combination of: (1) as prices rise during a housing market expansion, flippers undertake more complicated and time-consuming flips (2) less experienced flippers enter the game, and can’t turn around flips as fast as more experienced flippers, or (3) tax-incentives encourage flippers to take advantage of market appreciation by holding onto properties longer.

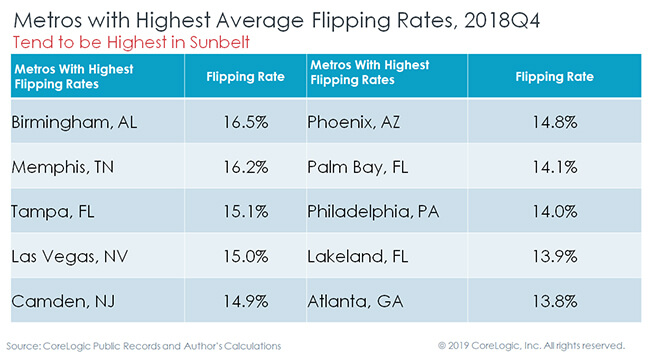

Using the two-year definition, we also find that flipping rates vary sharply across the country, tending to be highest in sunbelt metros and lowest in rustbelt metros, although the dichotomy doesn’t fit perfectly. For example, eight of the top ten metros with the highest flipping rate in the fourth quarter of 2018 were in the Sunbelt, with Birmingham, Memphis, and Tampa leading the pack with rates of 16.5, 16.2, and 15.1 percent, respectively. Just two of the top ten were in the rustbelt, with Camden and Philadelphia having rates of 14.9 and 14 percent.

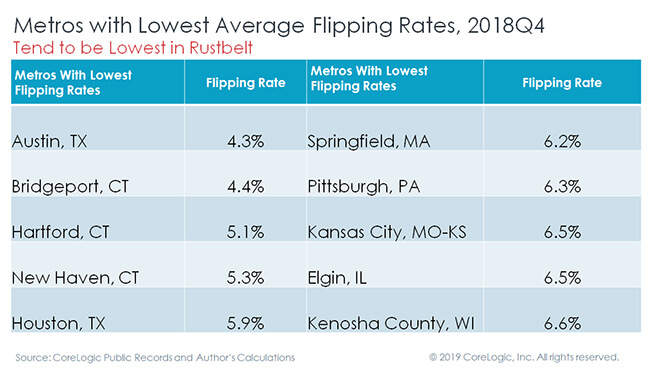

At the low-end, flipping activity tends to be lowest in Rustbelt metros, although two Sunbelt metros, Austin and Houston, make the list with flipping rates at 4.3 and 5.9 percent, respectively. Several metros in Connecticut also lag the country, with Bridgeport, Hartford, and New Haven showing flipping rates of 4.4, 5.1, and 5.3 percent. Five other Rustbelt metros make the list: Springfield, MA, Pittsburgh, PA, Kansas City, MO, Elgin, IL, and Kenosha, WI.

Returns Have Been on a Wild Flipping Ride

In addition to flipping rates, we also estimate economic returns to flipping. What’s the difference between an economic and normal (nominal) returns? Nominal returns are simply the percent difference between what an investor paid a property and what they sold it for, and economic return is the return that excludes opportunity costs, which in the case of flipping is general home value fluctuation. By using economic returns, we can get an idea about whether flippers are adding value of whether they are speculation on market appreciation. See our endnotes for a clarifying example.[iii]

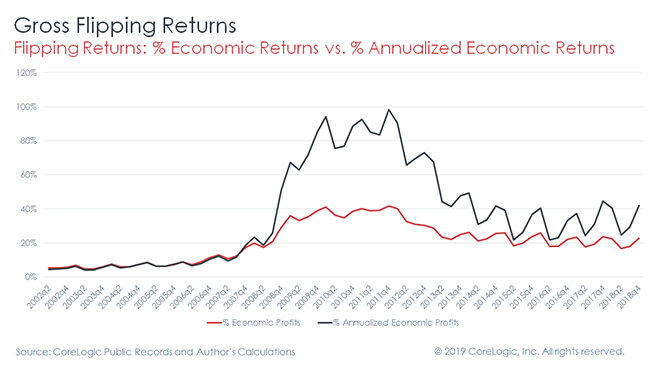

Nationally, we find that gross economic returns in the U.S. have been on a wild ride over our study period. From 2002 – 2007, both economic returns and annualized economic returns (the latter of which controls for the length of a flip) hovered around 4-5 percent. Because closing costs when selling a home are anywhere from 5-8 percent, these findings suggest that the only other way that flippers were trying to make money was by speculating on home value appreciation (remember, economic profits exclude home price appreciation).

After 2007, returns skyrocketed for flippers to a median of around 40 percent (and near 100 percent when annualized), presumably because they were able to purchase distressed properties at deep discounts and quickly resell them at a profit. The fact that annualized returns diverge significantly from non-annualized returns suggests that flippers were quickly reselling their acquired properties, and indeed we find that the median days of flipped home decreased sharply from over 300 days in the mid-2000s to just under 200 days during the foreclosure crisis. Since then, the median time of a flip has rebounded slightly to around 220 days. This shift during the recession caused the annualized returns on home flipping to spike.

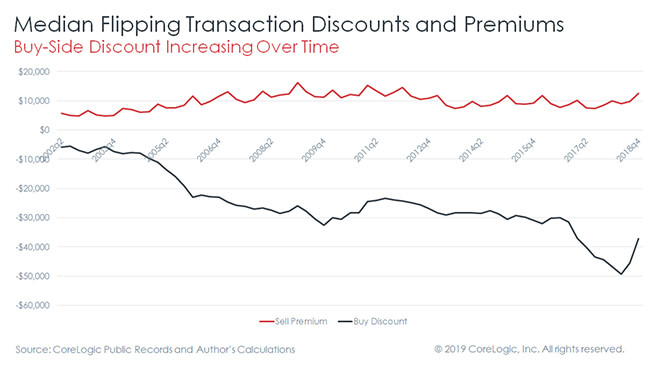

As mentioned above, we also find evidence that flippers are shifting away from price speculation and toward adding value to properties. How do we know this? By combining CoreLogic’s public records data with our robust statistical models, we can estimate the discount that a flipper received on a property when they purchased it, and the premium they received when they sold it, relative to similar properties that weren’t flipped. These two metrics, along with market appreciation, are the three ways that flippers can make money on a home.

Just like we found that flippers were likely relying on price speculation from 2002 – 2007, we also find that they weren’t particularly good at buying properties at a discount or selling them at a premium relative to other non-flipped but sold properties during the same time period. Since then, we’ve seen growing signs that flippers are getting increasingly good at buying properties at a discount while the premium they’re selling for has remained mostly constant. This is yet more evidence that flipping today is less risky and less speculative than during the 2000s.

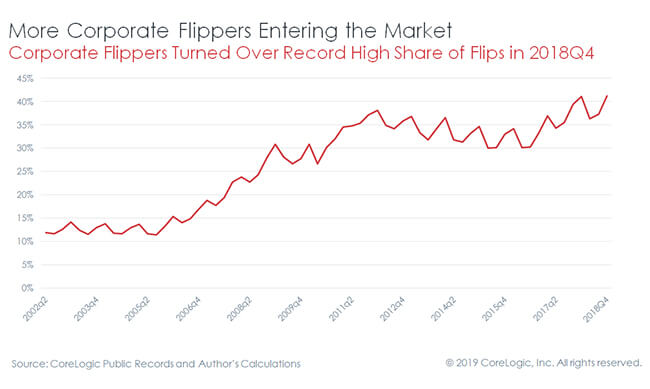

What’s more, the trend away from speculation and toward value-add might be due to an entrance of more experienced, professional flippers into the market. To explore this trend, we looked at the share of flipped homes that were sold by a business entity, such as an LLC, INC, or CORP, rather than by an individual. The trend has clearly been upward, with the share of flipped homes rising to a series high of 41.2 percent in the third quarter of 2018 from a series low of 11.4 percent in the third quarter of 2005.

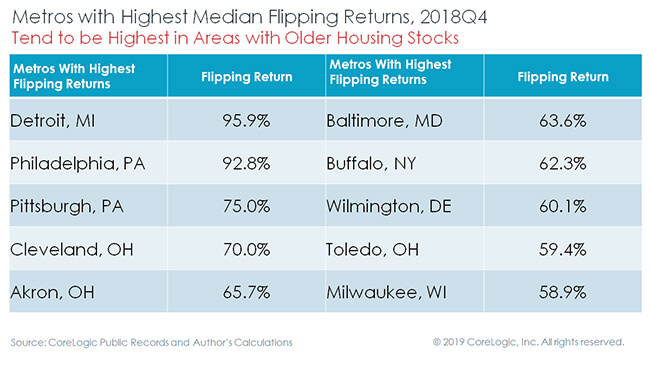

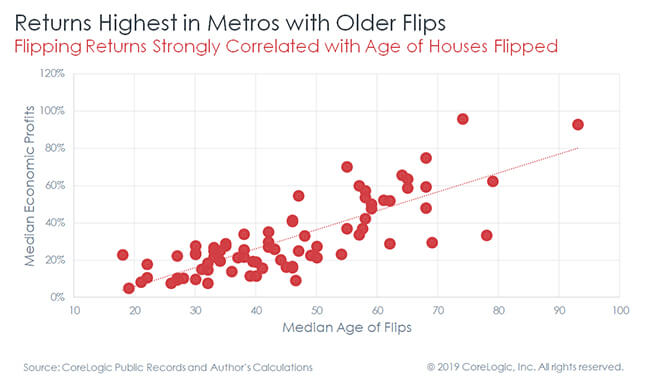

Returns Highest in Areas with Older Housing

Like flipping rates, we also see substantial variation in economic returns to flipping across U.S. housing markets, with returns highest in the Rustbelt and lowest in the Sunbelt. At the high end, returns are highest in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh with returns of 95.9, 92.8, and 75 percent, respectively. The other seven markets with the highest economic returns to flipping are in Ohio, Maryland, Delaware, Wisconsin, and New York with returns ranging between 58.9 and 70 percent, respectively.

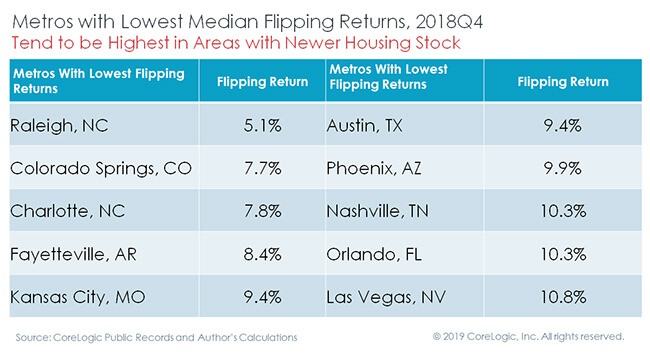

On the low end, flipping returns tend to be lowest in area that have newer housing stock. For example, the three markets with the lowest returns are Raleigh, Colorado Springs, and Charlotte, with returns of 5.1, 7.7, and 7.8 percent, respectively. The other seven markets with the lowest economic returns to flipping are in Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, Arizona, and Tennessee, Florida, and Nevada, with returns ranging between 8.4 and 10.8 percent, respectively.

We can see the relationship between age of homes flipped and economic profits by plotting the median age of home flips against the median economic profits of the 78 markets we have estimates of economic returns. The relationship is quite strong from a statistical perspective, with a R2 coefficient of 0.64. This means that 64 percent of the metropolitan-level variation in economic profits can be explained by the variation in the age of homes flipped.

Does this mean that home flippers are reaping more net profits in these older markets? Not so much. While gross economic returns are highest in places with older flips, they don’t capture the amount of money that flippers invested into the flip. On the contrary, flips undertaken on older homes likely require more capital to bring the home up to market standard than newer homes. Such updates might include costly improvements to electrical systems, plumbing, foundations, and roofing. What this does tell us is that flippers are likely to reap substantial discounts when buying properties with such deferred maintenance. In future iterations of our work on flipping, we’ll focus more explicitly on using our vast databases to estimate what improvement were made on a given property, the costs of such work, and thus the net economic profits earned by flippers.

For a more detailed description on the methodologies used in this analysis, please see the full white paper to be presented at the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association National Conference in May 2019 here.

[i] CoreLogic defines flipping as the purchase of a property with the intent to sell within a two-year period for profit. CoreLogic uses the 24-month definition as that is the Internal Revenue Service’s threshold for when real estate holdings could be considered owner-occupied and thus eligible for capital gains exemptions. The author diverges from previous CoreLogic work on flipping that uses a 12-month definition. This is because 12-month flips only capture flips that are subject to short-term capital gains tax, whereas properties flipped but held for 12-24 months are considered investments but subject to long-term capital gains tax. Since long-term capital gains tax rates tend to be lower than short-term capital gains tax rates, using the 24-month definition thus allows for a much broader analysis of investment in, and returns to, home flipping activity since some flippers may choose to hold properties longer than 12 months so that they may pay the lower long-term capital gains tax rate.

[ii] CoreLogic measures returns as the annualized economic returns to flipping, which considers the opportunity costs of a flip (price growth of similar houses that weren’t part of a flip), any market discount the flipper received on the purchase of the property, and any premium the flipper received on the sale of the property. Because CoreLogic does not observe the capital expenditures that an individual flipper deployed to undertake any renovations or repairs, our estimates of returns represent the upper bound of a return.

[iii] Consider this example: an investor purchases a property for $100,000 and sells it a year later for $200,000 after spending $50,000 on renovations. In this case, they earned a 100 percent gross return and 50 percent net return. However, over the same year, an identical house next door that didn’t have any work done to the property went up in value by $25,000. In this scenario, the gross economic return to the investor would be 75 percent, since we exclude the $25,000 the flipper would have made just from market appreciation. Considering the $50,000 the investor put into the property as well as the $25,000 market appreciation means the flipper earned $25,000, or 25 percent, net economic profit.

© 2019 CoreLogic, Inc. All rights reserved.